Before starting to learn any language, there’s something you can learn that will make acquiring excellent pronunciation much easier for any language.

I’ll illustrate with an example. Imagine you’ve just started to learn Swedish, and you’ve encountered the word “sjuksköterska”. Imagine you didn’t have access to a recording. How would you know how this word is actually pronounced? I could tell you that it sounds something like “hwookhertershka”, but that isn’t much help at all.

Alternatively, I could tell you that it’s pronounced /ɧʉːkɧøːtɛʂka/, or even [ˈxʷʉ̟ʷːkˌxʷœːtɛʂkʲa], depending on how specific I was willing to get. If you had the right set of background knowledge, these transcriptions would tell you all you needed to know about the pronunciation of this word, and you could pronounce it with a native-like accent immediately.

The system I used to transcribe the pronunciation of this word is called the IPA, short for the “International Phonetic Alphabet” (managed by the “International Phonetic Association”). Check out this interactive IPA chart to get a feel for what the IPA is, and keep reading to learn more about why you should learn it. Just click on the different symbols to get an idea of all the different sounds the IPA can transcribe.

This is a set of symbols that can describe the sounds of any language without a bias towards a particular language; the idea is that these can describe English phonology just as well as Swedish or even Mongolian phonology.

The IPA is a set of symbols that can describe the sounds of any language.

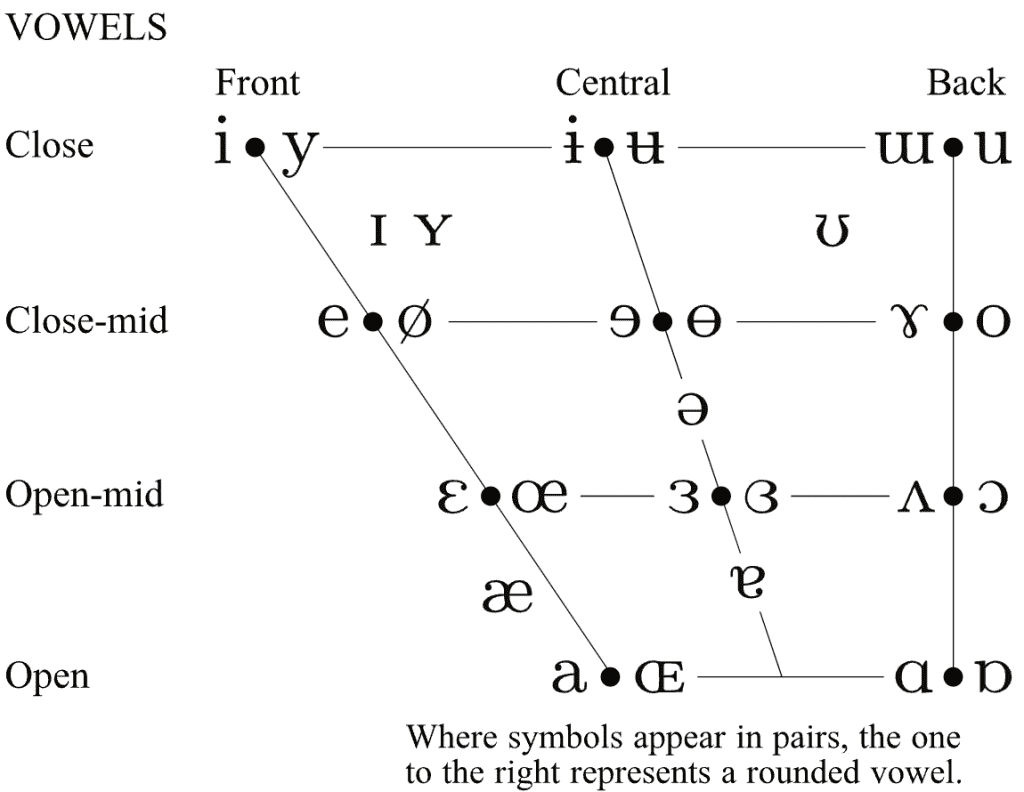

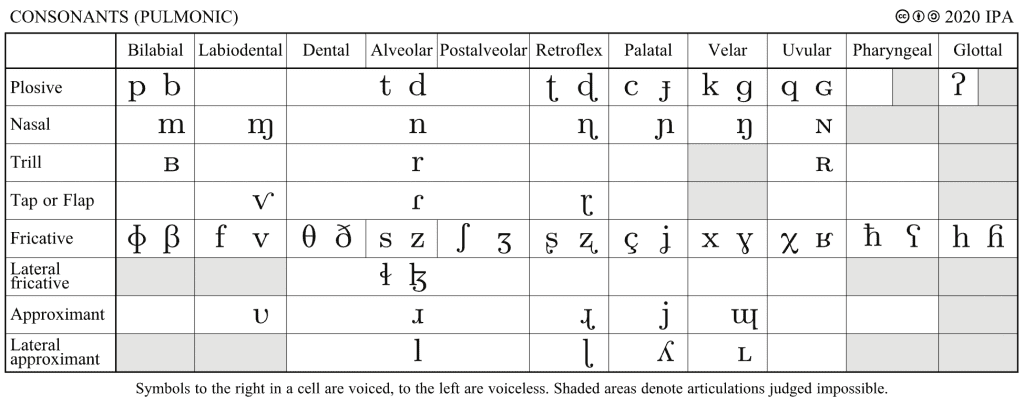

Here’s a couple screenshots of the official IPA chart:

Vowels

Consonants

This post will explain why it was created and why you should learn it.

English letters have too much ambiguity

You might think to yourself, “Why don’t we just use the English letters to transcribe things, wouldn’t that be simpler?”

The reason this wouldn’t work is because English letters can have different sounds, depending on the word they’re used in. Or put differently, a single letter can have multiple sound values. As a result, it’s very hard to accurately communicate sounds using pure English letters.

For example, take a look at the English words “win”, “white”, and “wide”. The letter “i” in each of these words has a different sound (for most northern American English accents). Since it could mean 3 different sounds, it would be difficult for the reader to know which sound the “i” is supposed to represent.

Another English letter that has multiple sound values is “a”. For example, the words “apple” and “ate” have different sounds for the same letter “a”.

Some more examples of English letters having multiple sound values are:

- “a“: “apple” and “ate”

- “u“: “putt” and “put”

- “t“: “water”, “take”, and “fit”

As it turns out, there are tons of letters like this in English that have multiple sound values. To illustrate this point further, there’s a fun example of how confusing English spelling is: the nonsense word “ghoti”, meant to be pronounced the same as “fish” according to the following principles:

- “gh” is pronounced as it is in the word “enough” or “tough”

- “o” is pronounced as in the word “women”

- “ti” is pronounced as in the word “nation”

The point this word is meant to illustrate is that English spelling is far from a clear writing system. This being the case, it does not work well to illustrate the pronunciation of words in other languages.

English spelling is far from a clear writing system and does not work well to illustrate the pronunciation of words in other languages.

The key take-away from this section is that relying on English letters to communicate pronunciation is very confusing, because the same letter (for example “i”) can have multiple sounds, so it’s difficult to communicate which pronunciation you have in mind.

The IPA: one letter, one sound

To solve this problem, the IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) was created. In this alphabet, every single letter has only one sound it can represent. For example, the letter “i” in the IPA would only represent the vowel sound in the word “wheat” (transcribed as /wiːt/ in the IPA).

Some examples of IPA transcriptions of confusing English words (the letters inside the slashes are IPA) in my dialect of American English would be:

- “fish”: /fɪʃ/

- “apple”: /ˈæp.əl/

- “ate”: /eɪt/

- “water”: /ˈwɑtəɹ/

Symbols like “æ“, “ɪ“, and more are all IPA letters, and are used to represent the sounds in the above words. I will detail exactly how these work in an upcoming post, so stay tuned!

Thanks to the IPA letters having just a single sound value, with a knowledge of IPA, there would be no confusion on how to pronounce these words even if you don’t have access to recordings.

Transcribing non-English sounds

Here’s another reason the IPA is useful: it allows us to transcribe sounds that don’t exist in English (or most other languages that use the Latin writing system), such as the Arabic consonant “ق”.

“ق” is written as /q/ in the IPA, and represents a sound that doesn’t even exist in English.

Since it doesn’t exist in English, just English letters would not be sufficient to transcribe it, since there’s simply no letter or letter combination that would actually explain how it’s pronounced.

This sound exists in all these other languages, too, so there’s clearly a need for a consistent way to describe it. Using the IPA’s /q/ allows us to communicate the sound value without any difficulty.

Solving confusing writing systems

Imagine being an English learner and encountering the following words: “thought”, “through”, “though”, and “plough”. The “ough” combination, in addition to being a very confusing letter combination to begin with, also has a different sound value in every one of these 4 words:

- “thought”: /θɑt/

- “through”: /θru/

- “though”: /ðo͡ʊ/

- “plough”: /pla͡ʊ/

Thanks to the IPA, however, you can glance over the transcriptions for a word you have no idea how to pronounce, and understand exactly which sounds a particular word is made of.

Thanks to the IPA, you can understand exactly which sounds a word is made of.

This is especially useful for languages with a confusing orthography (like English or French) or for languages that use a writing system you might be unfamiliar with (such as Arabic or Hindi).

To expand on the Arabic example, there’s a couple challenges learners face when learning to read Arabic:

- It’s a totally unfamiliar writing system, and it’s hard to remember the letters at first.

- Arabic does not write short vowels. For example the word for “France” in Arabic, which is pronounced /fa.ran.saː/, is written (in Arabic letters) as “frnsa” (without the /a/ sounds).

The result is that when you see an Arabic word without an IPA transcription, it can be very challenging to know how it’s actually pronounced.

Similar issues arise when learning other writing systems like that of Hindi, Thai, Mongolian, etc. There are tons of writing systems in the world that aren’t actually very good at communicating how to pronounce words accurately, instead expecting the reader to simply remember how words are pronounced.

Writing systems that are very easy to read such as Spanish or Italian are actually very rare, so it’s generally very useful to be able to read IPA transcriptions to know for sure how a word is pronounced.

To summarize, learning the IPA allows you to sidestep the issues presented by confusing, ambiguous writing systems that don’t give you enough information to actually know how a word is pronounced. With the IPA, what’s written is exactly enough to know how the word is pronounced. You never have to guess or be unsure.

Correct mental sound categories

Another benefit learning the IPA has is that it forces you to think in terms of the correct sound categories for the language you’re learning.

Every language has a finite set of sounds that words can be made out of. For example, American English has 24 possible consonant sounds and 14 vowel sounds. Every native speaker instinctively knows which sounds a word consists of, so if you want to reach the same level, it’s important to be able to do so as well.

Put another way, if you want to have a native-like accent, you should know exactly which sounds a word consists of. The best way to do this is to look up the IPA transcription for every word you encounter.

If you don’t do so, you run the risk of having mixed up mental categories for the sounds of the language you’re learning. For example, you might mistakenly assume that /æ/ (as in “bat”) and /ɛ/ (as in “bet”) are the same sound in English because they sound similar to you, especially if you come from a language like Russian that doesn’t have this distinction.

You could practice pronouncing “bat” and “bet” over and over again, but if you’re mistakenly pronouncing both with /ɛ/ because you don’t hear the difference, you’re just wasting your time. On the other hand, if you looked both words up from the start, you’d know that one has /æ/ and one has /ɛ/.

Knowing the IPA allows you to always learn a word with the correct pronunciation, and never mistakenly pronounce things with the wrong sound. This concept of mental categories is a hugely important one for perfect accents that I rely on heavily and will continue to expand on in future articles.

Advanced pronunciation information

Another benefit to learning the IPA is that it unlocks very precise phonetic transcriptions that can you tell you exactly how a word sounds without even any audio to accompany it! This section is a little advanced, so I’ll be publishing more articles on this concept later to help you understand.

The IPA can be as specific as you want it to be, and is capable of communicating extremely precise pronunciation details.

For example, given the precise IPA transcription for the Swedish word “sjuksköterska”, [ˈxʷʉ̟ʷːkˌxʷœːtɛʂkʲa], I could pronounce it with a very passable Swedish accent, even if I’d never heard the word before in my life.

This makes acquiring a native-like accent very efficient, because you no longer have to rely on drilling audio recordings and hoping you’re saying things right. If you look at [ˈxʷʉ̟ʷːkˌxʷœːtɛʂkʲa], you have all the information you need to position your mouth, lips, tongue, and throat correctly to get the sounds right from the start.

Combining this precise information with audio recordings is one of the techniques I’ve used to develop a perfect accent in many different languages, and I highly recommend you make use of it as well.

Note that understanding the nuances of more precise transcriptions like this requires an understanding of “phonetics“, the branch of linguistics that deals with describing linguistic sounds in a precise, scientific way. For example, rather than describing the French “r” sound as “guttural”, “throaty”, “phlegmy”, or even “nasal” (very wrong), we can instead precisely describe it as [ʁ], a “voiced uvular fricative”, with a tendency to “devoice” into [χ], a “voiceless uvular fricative” when next to other voiceless consonants. This type of precise terminology, once mastered, is another key to acquiring a native-like accent in any language.

I will be publishing more articles on this topic, so stay tuned and don’t forget to subscribe!

Just recordings are not enough

Using recordings of native (or highly advanced) speakers to work on your accent is a fantastic strategy to work on your accent, but unless you’re one of a few very gifted people, you won’t be able to reproduce the recordings 100% correctly.

The only consistent way to reach a native-like accent is to have a solid understanding of the IPA and combine that with audio recordings or listening to native speakers. The IPA gives you the background information and a mental structure to start with, and the recordings allow you to fine-tune the sounds you’re making to really match up exactly with native speakers.

As I describe in the “Advanced pronunciation information” section above, learning the IPA allows you to actually understand how speakers of a certain language perceive their languages’s sounds and produce them in a variety of different environments. This type of advanced phonetic understanding is how I consistently reach a native-like accent in the languages I study, so stay tuned for more articles on this subject.

Resources and further reading

Hopefully, by now, I’ve made a compelling argument for you to learn the IPA. If that’s the case, you might be wondering where you can start to learn it, and where you can read more about all these principles in general. I’ll try to provide some suggestions here for further reading, and I’ll also continue to cover these concepts in future articles!

Good descriptions of language phonology and the particular sounds of each relevant IPA symbol can be found on a language’s Wikipedia page in the format “[language] Language”, “Help:IPA/[language]“, and “[language] Phonology”. For example, for French:

- French Language: an overview of the French language, from history and geographic distribution to grammar and phonology

- French Phonology: a breakdown of the French sound system (making heavy use of the IPA)

- Help:IPA/French: a reference chart for which letters (and combinations) correspond to which IPA symbols, so that you can go from e.g. “vingt” (meaning “twenty”) to how it’s actually pronounced: /vɛ̃/. This also links to specific Wikipedia pages describing every single sound with an incredible amount of detail. For instance, even the page for a common sound like /b/, or the “voiced bilabial plosive” (as in “bat” or “boy”) has a diagram and technical explanations, and every other sound you can think of has a page with explanations and examples in different languages.

For an overall starting point, start with the “Phonetics” Wikipedia page.

Lastly, you can use Wiktionary as an online dictionary that provides IPA transcriptions for words in nearly every language.

Of course, I will also keep writing lots of content in this area, so make sure to subscribe to get notified of new articles!

Conclusion

In this article, I went over what the IPA is and the most important reasons you should learn it if you’re interested in acquiring a native-like accent in the language you’re learning.

Learning the IPA will allow you to:

- Always know how a word is pronounced, even with writing systems like English (confusing spelling) or Arabic (doesn’t write down any vowels in its words)

- Have clear mental categories for what sounds a language has and which words use which sounds.

- Understand the principles behind how sounds are produced and accelerate the process of learning to pronounce unfamiliar sounds correctly thanks to having a theoretical base to work from.

- Super-charge recordings with an “answer key” of what sounds are actually in the word so you can quickly sound like a native speaker (and also have no trouble with listening comprehension tests)

Take the time to learn the IPA and you’ll be well on your way to sounding like a native.